AI just explained my own research back to me. I was surprised by how it showed me the message I meant to say 10 years ago, but seemed to lose in the academic genre of the original articles.

I’m working on how to teach AI tools in my API documentation course. As part of my research, I thought I’d feed some of my technical writing articles from about 10 years ago into an AI tool, along with some contemporary work from others. I asked the AI to compare, contrast, and summarize them from various angles.

The results were interesting enough that I had to write about them here.

When AI becomes your editor

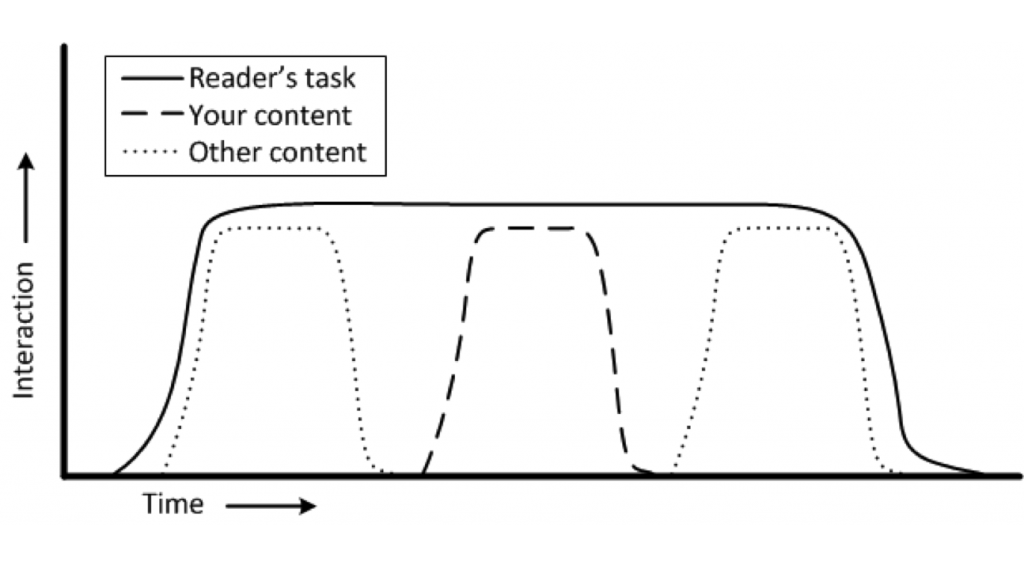

One summary took an analysis I’d buried in academic prose and flipped it into something useful. It linked the different documentation types commonly found in API Documentation to what readers are trying to accomplish:

Original version:

In Using Readers’ and Organizations’ Goals to Guide Assessment of Success in Information Websites (2015), we proposed this list of goals that readers could hope to accomplish in an informational site (e.g. documentation). Examples of each goal were presented later in the 12-page article.

- Reading to be reminded (Reading to do lite)

- Reading to accomplish a task in a website (Reading to do here)

- Reading to accomplish a task outside a website now (Reading to do now)

- Reading to accomplish a task outside a website later (Reading to learn to do later)

- Reading to learn (Reading to learn to use later or to apply with other information)

AI’s translation:

- Recipes and examples for “reading to do now”

- Topical guides for “reading to learn”

- Reference guides for “reading to be reminded”

- Support forums for edge cases and community help

- Marketing pages for pre-usage evaluation

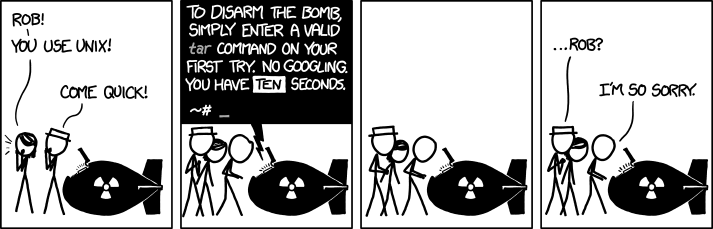

Then it got right to the point that I’d been dancing around for paragraphs:

Yet we typically measure them all the same way. Page views, time on page, bounce rate. That’s like using a thermometer to measure blood pressure. The tool works fine; you’re just measuring the wrong thing.

Ouch. But also: exactly.

The AI summary went on to suggest what matters for each content type:

Continue reading “Is your documentation ready for AI?”