This series looks at the different site interactions that readers have with informational sites and is adapted from the full paper on the topic that I wrote with Jan Spyridakis and presented at HCII 2015: Using Readers’ and Organizations’ Goals to Guide Assessment of Success in Information Websites. See the entire series

Reading to be Reminded

Reading to be reminded, or Reading to Do Lite, occurs when readers visit an informational site with the confidence that they already know most of what they need to know about a topic to complete their task, but they just need a refresher. Readers use the website as a form of offline information storage that they may use either online or elsewhere. By knowing the information is available online, readers are confident that they don’t need to remember the details, just where they can find them. Brandt et al. [1] noticed this pattern while observing software developers who “delegated their memory to the Web, spending tens of seconds to remind themselves of syntactic details of a concept they new [sic] well.”

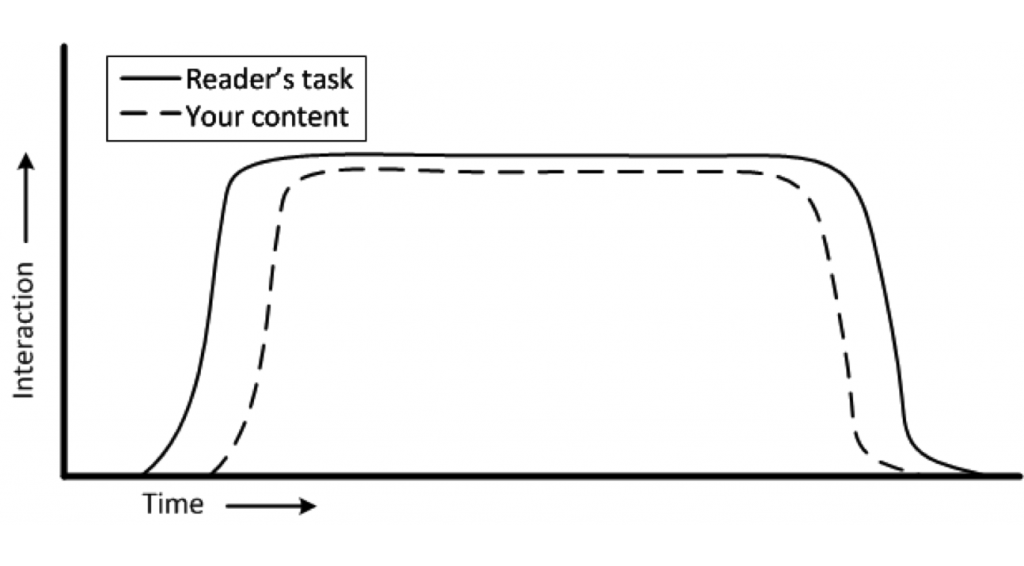

The figure shows how interactions of this type might relate to a reader’s task.

Because, as Redish [2] says, readers will read “until they’ve met their need,” readers will spend as little time in the site as they need interacting with the content. Once they have been reminded of the information they need, they will return to their original task.

Topic design principles needed to serve this interaction include making the content easy to find, navigate, and read. Visible headings and short “bites” and “snacks” of information [2] are well suited to such a goal. However, my research in developer documentation says that these guidelines depend on the specific context–a reminder to know your audience. Knowing your audience is also key to using the terms they will recognize.

Website-based metrics are not particularly helpful in determining the quality of the readers’ interactions. A good time-on-page value, for example, might be short–to the point of appearing to be a bounce, or it might be long. The number of times a page is viewed also has an ambiguous meaning when it comes to understanding the quality of the readers’ interactions.

At the same time, the readers’ engagement and focus on their primary task (the one that sent them to this content) means asking qualitative information about their experience is likely to be seen as a distraction. Asking about the reader’s experience should be done soon after the interaction and with as brief of a satisfaction questionnaire as possible—perhaps only one question, such as “Did this topic help you?”

[1] Brandt, J., Guo, P.J., Lewenstein, J., Dontcheva, M., Klemmer, S.R.: Two Studies of Op-portunistic Programming: Interleaving Web Foraging, Learning, and Writing code. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, ACM, pp. 1589–1598 (2009)

[2] Redish, J.: Letting Go of the Words: Writing Web Content that Works (2nd ed.). Morgan Kaufmann, Elsevier, Waltham, MA (2012)