As More docs on API docs described, it’s mostly academic authors writing about API docs, but only by a narrow margin. As I was reviewing the articles I found, my impression was that only men were writing about API documentation.

Because impressions can be mistaken, I went through the articles and reviewed all the authors to determine their gender, insofar as I could. Because this information is rarely reported with the articles, I had to do some digging.

Most of my determination of an author’s gender is based on the authors given name; however, where available, I used their portrait or other references to confirm. For the names that had a recognizable (to me) gender preference, I assigned them accordingly. For those I couldn’t easily tell, I searched for the author’s profile on Google Scholar, ResearchGate, and just plain-ole’ Google to find a social media page. However, after all that, I could not make a credible determination for a little over 5% of the authors so they show up as unknown in the pie chart.

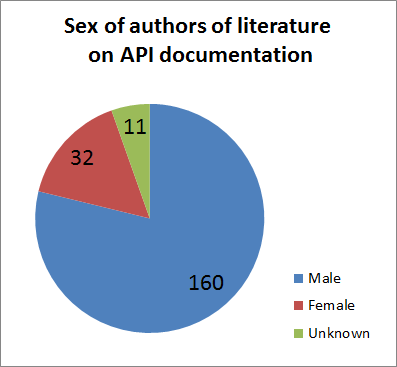

It turns out that my bibliography of 112 articles has a total of 203 unique authors; at least 160 (79%) of which seem to be men, while at least 32 (16%) seem to be women. Or, seen another way,

1 author in 6 who has written an article on API documentation is a woman.

That ratio is roughly consistent with the population of software developers reported in surveys such as Women in Software Engineering: The Sobering Stats (1/6) and 2018 Women in Tech Report (1/7).

So, what does this say?

I’m not sure. It seems like a case of: hey, 1 in 6 authors of articles about API documentation is a woman, which is in the same proportion as the software development field. And, hey, only 1 in 6 authors is a woman, which is in the same proportion as the software development field. Also noteworthy, the earliest article in my list was authored by a woman.