Here it is, Wednesday, just four days after the hackathon and my post-hackathon hangover is finally abating. Don’t get me wrong, the hackathon was a great party. Like so many great parties, however, there’s often a morning after to get past.

Here it is, Wednesday, just four days after the hackathon and my post-hackathon hangover is finally abating. Don’t get me wrong, the hackathon was a great party. Like so many great parties, however, there’s often a morning after to get past.

Taking stock

I’ve already chronicled the experience sufficiently, so I’ll take a moment to indulge my post-hackathon hangover. This reminds me of my timer project. I’m seeing a pattern…

A demo is not a prototype

For as exciting as the hackathon was, the result was barely a protoype and, in all honesty, it was barely a demo. (It was a great pitch, though!) So, for all the accolades, there are a lot of problems that remain to be solved before the project is close to anything that could be deployed. Been there. Done that. Quite a few times, now.

That said (as the hangover fog begins to clear with the light of a new day…several days later), there were some valuable lessons to hang on to from the experience.

Less really is more

On top of our team’s focus and cooperation, I would attribute much of our success in the hackathon to our keeping the sample app and corresponding demo focused on their core values. Throughout the event, we explored various corners of additional features and context, which is good, but we also focused on the goal and used those explorations to shape the final product, not be included in the final product. Remember, the product of the hackathon is a pitch.

Less is more, until it’s less; and that’s the sweet spot.

I’m here to tell you that it is VERY DIFFICULT to throw stuff overboard to keep the ship afloat (one look into my garage will prove that point), but sinking due to an excess of good (and great) ideas, doesn’t help anyone (between you and me, building a larger garage doesn’t always help, either).

Keep your eye on the prize.

There’s a need

The positive reception to the idea we pitched shows that the idea has some legs. The audience immediately recognized the need as clear and they saw the value in the solution we presented.

The importance and significance of that cannot be overstated. i.e.

Having a recognizable value IS HUGE!

There’s an opportunity

The post-hangover question to ask is, “how to realize the opportunity?” The solution will cost something. It’s not clear how much, though. The pitch and and overwhelmingly positive response from the audience surely will help appeal to and attract additional supporters, such as supporters, developers, designers, beta-testers, and the like. There might also be some interest in and market for a similar product in commercial applications. So..

What’s next?

That remains to be seen, but, for now, we have a website.

Some kinda fun.

I made it to the top-10 most viewed in General Aviation, this week.

I made it to the top-10 most viewed in General Aviation, this week.

I’ve suggested in various venues that aspiring (and experienced) tech writers look into open-source projects to find projects they can use to build out their portfolio. In addition to making your portfolio a better place, working on civic-tech open-source projects has the extra advantage of helping to make the world a better place.

I’ve suggested in various venues that aspiring (and experienced) tech writers look into open-source projects to find projects they can use to build out their portfolio. In addition to making your portfolio a better place, working on civic-tech open-source projects has the extra advantage of helping to make the world a better place.

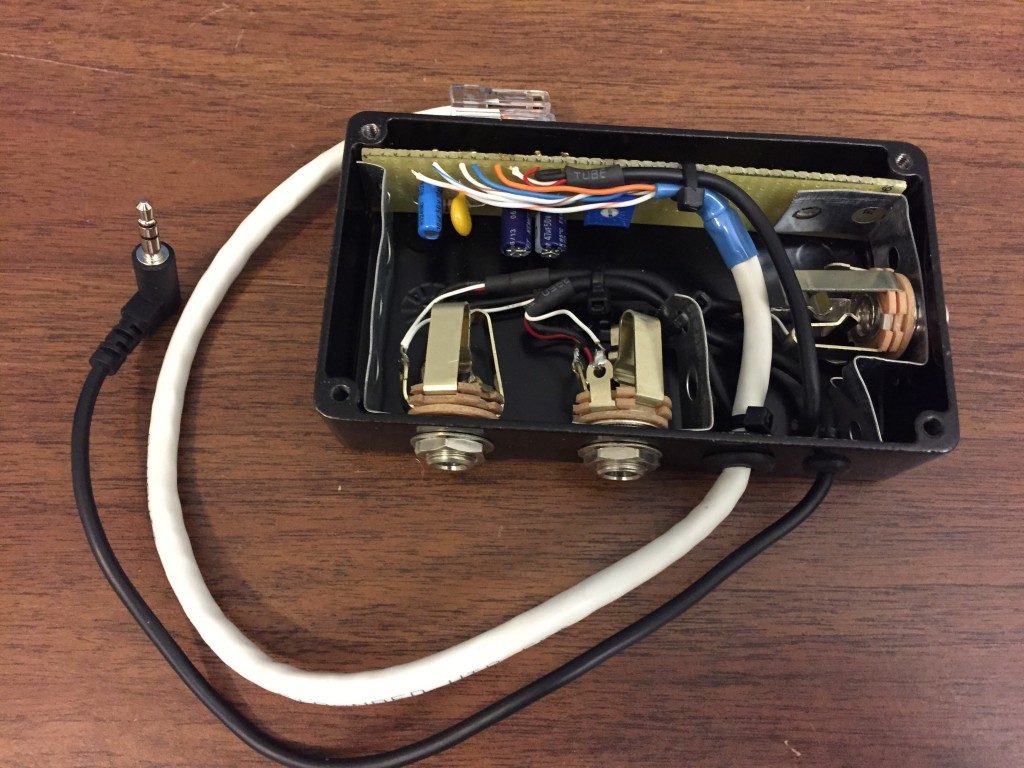

Catching up on long-overdue blog posts, here’s a project I did a couple of years ago to adapt an aircraft headset to my

Catching up on long-overdue blog posts, here’s a project I did a couple of years ago to adapt an aircraft headset to my