Recently, my ham-radio hobby took a turn into the world of QRP (pronounced, cue-are-pee) as the hobbyists call it. QRP is a world where portability and low-profile are preferred over the big and large. The name is from the set of three-letter abbreviations adopted by amateur radio enthusiasts that codify a variety of ham-radio situations and each code start with the letter Q.

QRP means low power.

While General and Extra-class amateur radio operators are licensed to operate on the short waves (below a frequency of 30 MHz) using a transmitter power of 1,500 watts, power levels of 5 watts or less are used in the world of QRP. For comparison, AM broadcast stations transmit with up to 50,000 watts and FM broadcast stations transmit with up to 100,000 watts.

QRP stations are essentially whispering.

What’s the attraction? Mostly that it’s more difficult. QRP stations can’t rely on output power alone to help push their signals into the world so amateur radio operators like to credit their skill as being the differentiating factor. While there’s some truth to that, there are also many other factors the help the signals along the way.

One benefit of QRP stations is that they are very small, and comparatively lightweight making them easy to carry. The radios are generally battery-powered, easy to pack, and easy to carry. More traditional, home-based ham radio stations use a 100-watt radio, such as the one I use from my house. Unlike my lightweight, battery-powered, QRP radio, my ham radio at home requires an AC power supply or a very large (i.e. heavy) battery. A so-called legal-limit, 1,500-watt station requires an electric power that is comparable to what you would use for an electric clothes dryer–making it something less than portable. For the “ham on the go,” QRP is an easy way to take your hobby on the road.

Because QRP operations are the ham-radio equivalent to whispering, not everyone can hear you. However, with the right combination of weather conditions, frequency, antenna, skill, and luck, 5 watts of radio-frequency energy can go quite a long ways–even further if the receiving station has a powerful antenna to help hear your whisper among the other stations.

My QRP station

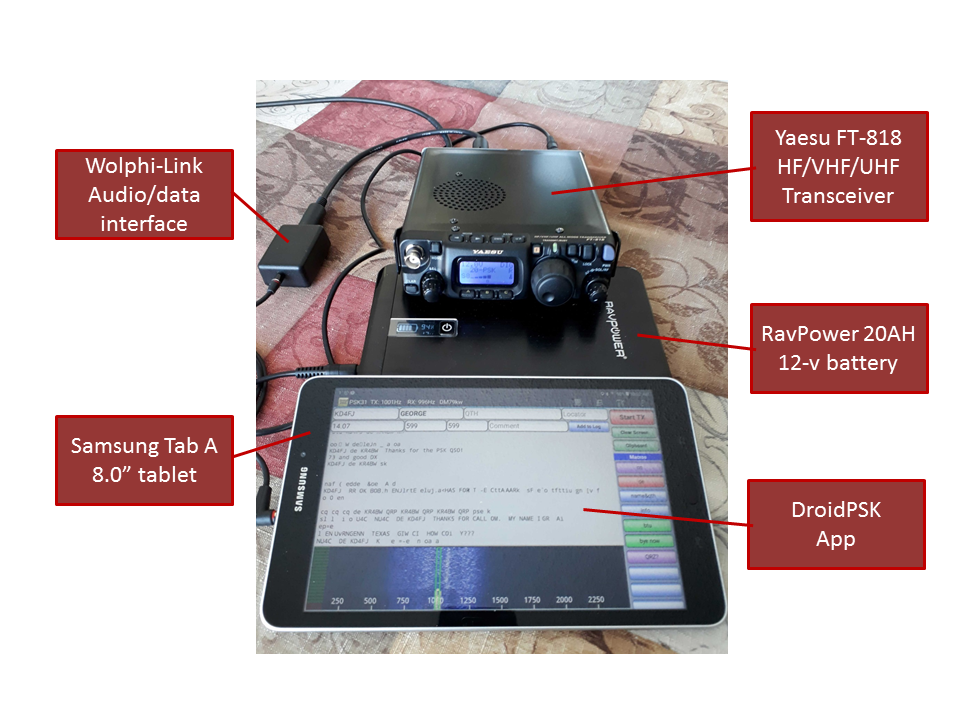

My portable station, in the photo below, consists of:

- A ham radio (Yaesu model FT-818)

- A battery to power it (although the FT-818 has a battery of its own, as well)

- An antenna (not shown)

- An “encoder/decoder” such as:

- A microphone & speaker for voice

- A Morse-key and speaker for Morse code

- A tablet or some type of computer for digital communications

The detailed parts list is included at the end of this post.

The portable station shown in the photo weighs about 5 pounds and the antenna I have weighs about 6 pounds. Smaller and lighter antennas are possible, but they tend to need more work to set up. With this 11-pound, battery-powered station, I’ve been able to send and receive messages between Georgia and places as far as Seattle (it was a good day). In the short time that I’ve had it, I’ve seen a more common range of 1,000 to 1,500 miles on 14.070 MHz (in the 20-meter wavelength band of amateur frequencies).

As a comparison, the 100-watt amateur-radio station I took to Honduras for the medical mission my wife and I participated in weighed about 40 pounds, took up an entire suitcase, and required an AC outlet or a car battery (not included in the 40 pounds) to power it.

Ham radio conversations

While it’s been fun to take my hobby on the road, whispering has also been good for the soul. Operating QRP requires (and develops) some degree of patience. While I can’t talk to everyone I hear, the conversations I do have seem more valuable because they took some work to accomplish. Some days, it’s like I’m whispering into a void, while other days, such as today, several people answered my first call. It’s a lot like Forrest Gump’s box of chocolates (but without the calories).

I put conversations in italics because the term has a slightly different meaning in ham radio. A conversation (QSO, pronounced cue-ess-oh in ham-radio circles) can be two people talking to each other as you might imagine two people conversing anywhere. However, voice signals are easily degraded by noise and other interference that my meager whispers can’t always overcome. Digital communication modes tend to tolerate more signal degradation than voice so they are increasingly popular in QRP operations. Morse code is the lowest-overhead communication mode and is the mode preferred by the more dedicated ham-radio enthusiasts.

Digital communication modes

I haven’t learned Morse code well enough to try to communicate with it, so I stick to the digital modes, which require a tablet or a laptop to do the encoding and decoding, hence the tablet in the photo. Practically, digital modes like PSK-31 (the type of encoding and modulation used to transmit and receive the signals) are essentially an interactive chat where one person types a message on one side as the person on the other side reads it. Chatting, basically.

FT8 is another popular digital mode, but you can barely call it’s limited, highly structured protocol a conversation. FT8 amounts to a mutual, albeit passing, handshake that takes place in less than a minute or two and amounts to only acknowledging that you acknowledged each other.

An older digital mode is that used by the old radio-teletypes, is called RTTY, it was used 70 years ago by teletype machines to communicate around the world. While the teletype machines themselves are hard to come by (and very noisy), the communication protocol is still popular–and supported by my tablet.

QRP on the road

So, for the past several weeks, I’ve been distracting myself by putting together a portable station and I’ve taken it on the road to field test. I have some notes and some ideas to make it a bit more portable and a bit easier to assemble and transport.

- Longer antenna cable: 25′ is light but limits the options. I have a 50′ cable but that seems too long, so maybe I’ll try 35′?

- A stand to prop up the front of the radio. Two things I’ve noticed while using the radio in the field. I’m not the first to notice this, because there are many COTS solutions for this.

- The front of the radio needs to be propped up.

- The back of the radio needs about 2″ of protected space (i.e. room) to give the connectors on the back some room.

- The bigger screen of the tablet is easier than the smartphone to use for the digital modes (i.e. chatting by ham radio). While, a keyboard would be even easier to use, that’s one more thing to pack, so I’ve kept it out of the kit…for now.

- The FT-818’s internal battery lasts for a couple hours of digital chatting. The larger, external battery in the photo used about 10% of its charge per hour. Between the two, they would last all day. One project on the list is to add a solar panel to the mix to try and stretch that time even further–like into the night.

Each trip is different, so the ongoing challenge is to know how much to bring to be prepared and how much to leave at home to keep things portable. The following section describes my portable station as it is today.

My QRP station details

Here’s the detailed parts list of my current portable station:

- Yaesu FT-818 HF/VHF/UHF radio

- External battery (the model in the photo is no longer available, but it is similar to this current model)

- Wolphi Link Smartphone interface

- 6-pin to 6-pin mini-DIN cable

- Smartphone cable

- Samsung Galaxy Tab A 8.0 tablet

- Buddipole Vertical antenna

- Shock-cord mast (short)

- Mini shock-cord whip (9-section)

- Versa-tee

- Guying kit

- Versa-tee

- Accessory Arm (short x4)

- 25′ RG-58 Coax (but I think I’ll pack a longer one for some more flexibility)