Catching up on long-overdue blog posts, here’s a project I did a couple of years ago to adapt an aircraft headset to my Yaesu FT-857D ham radio. Aircraft headphones are optimized for the high-noise environment of an airplane—the earmuffs keep the ambient sound (noise) out and the microphone is designed to let only the pilot’s voice in. While I haven’t used my ham radio in a plane, the headset works well in other noisy environments.

Catching up on long-overdue blog posts, here’s a project I did a couple of years ago to adapt an aircraft headset to my Yaesu FT-857D ham radio. Aircraft headphones are optimized for the high-noise environment of an airplane—the earmuffs keep the ambient sound (noise) out and the microphone is designed to let only the pilot’s voice in. While I haven’t used my ham radio in a plane, the headset works well in other noisy environments.

OK, but why an adapter?

A little history

Aircraft communication systems had their formative years in the 1930s and 1940s; so much of the communication technology used in today’s aircraft was designed to meet technical requirements established back in the ’30s.

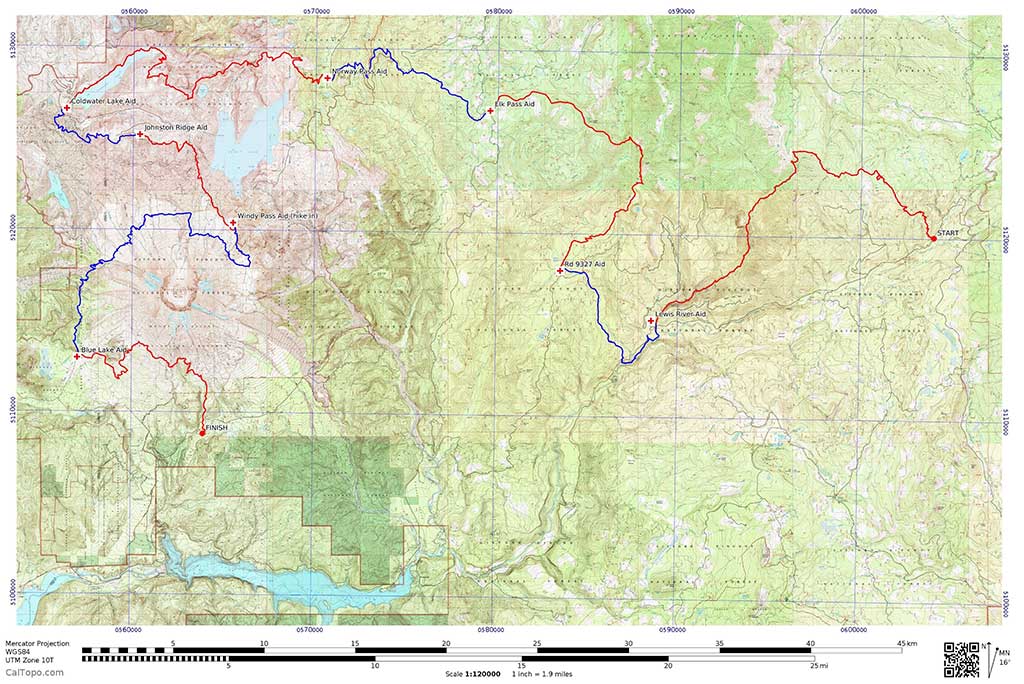

For this project, the microphone technology standards are what drive the requirements. The electrical standard for aircraft microphones is based on the carbon microphones used back in the formative years. Besides being available in the 1930s, carbon mikes are naturally noise cancelling and work well in an airplane. They also need some electrical current to work. This adapter provides the current necessary to make an airplane-compatible microphone work with a ham radio and it adapts the connectors–the headset’s connectors are also not compatible with those used by the ham radio.

The project

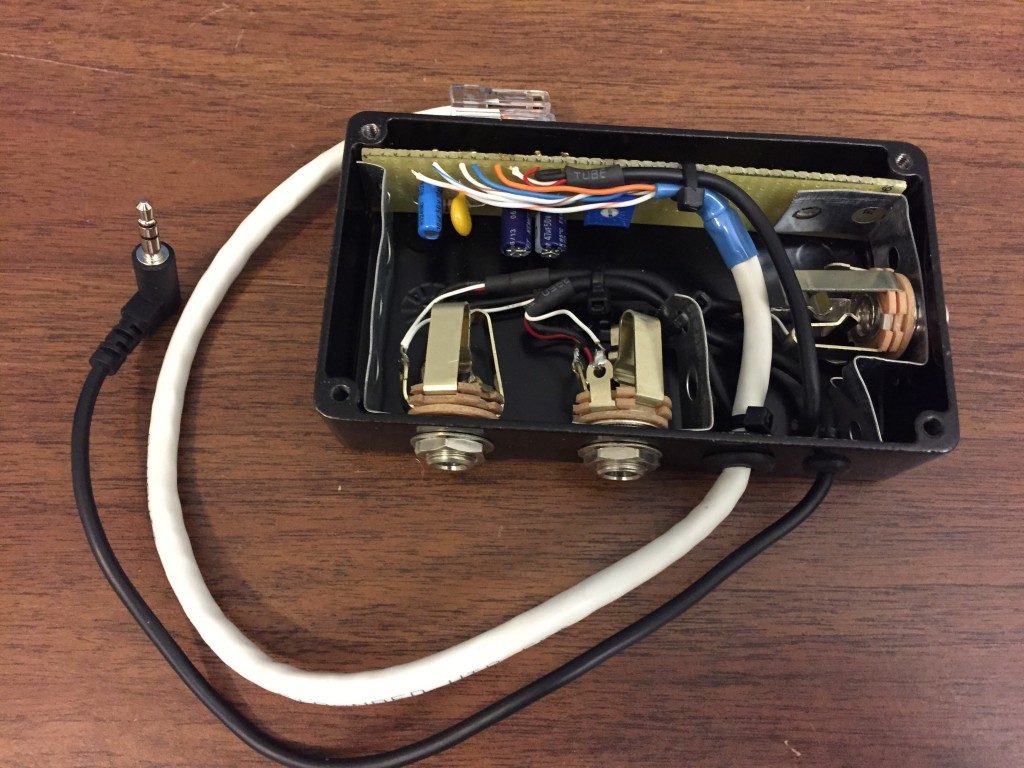

The design project was more mechanical than electrical. The headphones (speakers) on the headset are electrically compatible, so only a connector adapter is necessary. The electrical circuit used is a composite of several I found on the web and in QST, the magazine of the ARRL, and requires only a few components. Nevertheless, the hard work was in getting it all to fit in a box. Unlike my timer project, looks and durability were important design criteria.

Some of the requirements:

- The high-order bit: it had to adapt an aircraft headset to the ham radio.

- The adapter case had to support the stiff headset connectors.

- The case had to be as small as possible, but large enough for all the connections and cables.

- The cables and connectors had to survive multiple connections and disconnections.

- The case had to be removable but, when mounted to the radio, mounted securely.

The results

The end result came out rather well and has survived two years of domestic and overseas deployments. With any luck, it’ll survive as long as the timer project I described a while back.

HeadsetAdapterBox contains the mechanical drawings, circuit schematics, and parts list, if you’re interested in building one. (Some assembly required–actually, ALL assembly is required!)

Update

This topic has received a lot of traffic, lately, so I thought I’d add some additional links. I’ve not been able to find links to the ARRL references I mention above. When I do, I’ll add them here. Also, I don’t want to give the impression that I invented any of this. The circuit is very common. Mine derives from Aviation Headsets for Ham Radio, which derives from Aviation Headset Connected to FT-897, posted a few years earlier. As I recall, one reference I found for this application was from the 1990’s. I adapted these to my particular application and, if anything, my contribution to the project was in the mechanical design, more than the electrical circuitry. Along those lines, I will say that after the past few years of use, the industrial Velcro attachment method has proven to be quite reliable.

If I had to do it again, I would add an external speaker jack and switch. Plugging in the adapter to the radio’s headset jack disables the radio’s speaker. That’s great when you’re operating by yourself, but when there are people huddled around you who also want to listen (and you don’t want to give up the convenience and clarity of the headset), not being able to also output the audio to a speaker can make things awkward.

For your convenience, and to save you from rummaging through Google, here are some more links on the subject. You’ll notice they have a lot in common, with variations to accommodate their individual applications. Some of the pages were posted since my article, and they are in no particular order. They are here only to help you make the best adapter for your application. Enjoy!